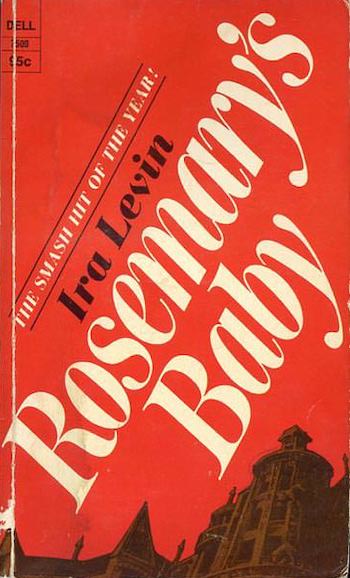

Ira Levin’s bestselling horror novel Rosemary’s Baby is a paranoid fever dream about patriarchy. The main character, Rosemary Woodhouse, is the target of a literally Satanic plot of rape, forced birth, and domesticity. She is, in other words, the victim of the same conspiracy of sexism, misogyny and male entitlement which targets all women in a sexist society. “There are plots against people, aren’t there?” she asks, with a plaintive insight.

But while Levin’s book is devastatingly precise in its analysis of patriarchy’s disempowerment and control of women, it isn’t exactly a feminist novel. In his 1971 book The Stepford Wives, Levin mentions Betty Friedan, Gloria Steinem, and talks directly about the growing women’s movement. But in Rosemary’s Baby, feminist consciousness is notably absence, which is part of why the novel is so bleak and terrifying. The narrative recognizes that Rosemary’s fate is diabolically unjust. But it offers no way out, narratively or theoretically. The devil’s victory is total not because he defeats feminism, but because he rules over a world in which feminist possibilities don’t exist.

The 1968 film directed by Roman Polanski is famously faithful to the novel, even down to much of the dialogue, so if you’ve seen that, the novel’s plot will be familiar. Rosemary and Guy Woodhouse are a young, attractive couple who move into The Bramford, a New York building clearly modeled on The Dakota. Rosemary wants children, but Guy insists they wait until he is more successful in his acting career. The two become friendly with their elderly, nosy neighbors, Minnie and Roman Castevet. Soon Guy gets a lucky break when a rival for a part in a play goes blind, and he immediately agrees to start a family, and they note the date when she’ll be most likely to conceive.

On that night, though, Rosemary passes out, and has a dream that a demonic creature is raping her. Guy says he had sex with her while she was unconscious. Her resulting pregnancy is difficult; the Castevets send her to a doctor, Abe Saperstein, who refuses to prescribe anything for the incapacitating pain. Though the discomfort eventually dissipates later in the pregnancy, she begins to think that the Castavets, Saperstein, and even Guy have been plotting to steal her baby for a Satanic sacrifice. She’s partly right—it turns out she has been raped by Satan, and her demon baby (who has “his father’s eyes”) is prophesied to lead the world into apocalyptic darkness.

Levin’s first novel, A Kiss Before Dying, from 1953, is the story of an ambitious young man who seduces and murders a series of women in pursuit of wealth and success. Rosemary’s Baby has more supernatural trappings, but at bottom the villain is once again not the devil, but the significant other.

Much of the genius of Rosemary’s Baby is in Levin’s quietly devastating portrayal of Guy as a soulless shell around a core of self-aggrandizement and egotism. We learn early on that Guy treats his wife’s best friend Hutch cordially not for Rosemary’s sake, but because Hutch corresponds with an influential playwright. In another offhand aside, Levin notes that Guy approves of Actor’s Equity “blocking the employment of foreign actors”—his ambition prompts him to deny others opportunities.

Guy’s focus on his career makes him inattentive at home. He’s constantly telling Rosemary he’s going to turn over a new leaf and treat her with more kindness and consideration. These protests sound reassuring the first time, but which quickly become ominously hollow when repeated: “Now looking back over the past weeks and months, [Rosemary] felt a disturbing presence of overlooked signals just beyond memory, signals of a shortcoming in his love for her, of a disparity between what he said and what he felt.”

Rosemary slowly comes to recognize that Guy does not love her, and will gladly sacrifice her health, safety, and bodily integrity for his career and ambition. But even when she realizes he’s her enemy, she has few resources to resist him. In part this is because the world is against her. Her neighbors spy on her, calling Guy home when she has a friend in her apartment, ensuring that she won’t have a chance to articulate, or even develop, her suspicions. Her doctor, Saperstein, pooh-poohs her chronic pain even as she wastes away. Rather than prescribe her medicine for pain, he bullies her when she admits to reading books about pregnancy, and even warns her against talking to friends. When she tries to get a second opinion, her husband refuses to pay. Other doctors defer to Saperstein’s professional reputation. The patriarchy is everywhere.

That “everywhere” includes inside Rosemary herself. Guy may be the main bad guy, but Rosemary herself is his best ally. Throughout the novel, she defines herself through a self-sacrificing domesticity which puts her husband and child first, and leaves little space for her own agency or even her own self-preservation.

For example, several of Rosemary’s friends try to get her to see another obstetrician for her pain, in one of the book’s rare portrayals of female community and friendship. Rosemary, though, immediately declares in a panic, “I won’t have an abortion.” As her friends point out, no one suggested she have an abortion. But she proactively refuses to consider the possibility, even though she has been suffering debilitating pain for months and her own health is obviously at risk. In prioritizing her baby over her own life, she is, unknowingly, offering to die for that patriarchal devil. Even Guy and the Castavets aren’t as loyal to hell.

Even more disturbing, perhaps, is Rosemary’s reaction when she is assaulted. Rosemary is more than half unconscious when the devil is summoned to rape her. When she wakes up, though, she has scratches on her back, which Guy explains by saying that he had sex with her while she was unconscious. He confesses, laughingly, to marital rape.

At first, Rosemary is, understandably and rightfully, upset. She feels betrayed and angry. But she quickly starts to make justifications for his actions, and to defend him better than he can defend himself. “What had he done that was so terrible? He had gotten drunk and had grabbed her without saying may I. Well that was really an earth-shaking offense, now wasn’t it?” The irony here is that it is an earth-shaking offense; the crime against Rosemary will literally bring about the apocalypse. What Guy did was “so terrible,” not least because it was done to someone so intimately invested in his goodness that she can’t accuse him, even to herself. At least, not until it’s far too late.

Rosemary’s colonization by patriarchy goes even beyond verbal acquiescence. Levin frames her self-betrayal as biological. Only partly conscious, she enjoys the devil’s rape of her; describing the demon inside her as “painfully, wonderfully big,” before she orgasms.

In the final act of the novel, the devil worshipers take Rosemary’s baby from her after it is born; they tell her it died. But she doesn’t believe them, and eventually discovers the child alive in her neighbors’ apartment. When she first sees it, she finally learns that her child is the devil, with yellow eyes and claws on hands and feet.

She is at first repulsed—but then her mothering instincts take over. When the demon baby begins to cry, she understands immediately that it is because his caregiver is rocking his bassinet too quickly. The baby has a quasi-mystical connection with her even though he has been separated from her for days since the birth. “He’s stopped complaining,” Roman says. “He knows who you are.” Rosemary’s link to her child is animal and spiritual. The devil patriarchy is her truest self, and she cannot escape it. It knows her, inside and out. In Levin’s nightmare vision, the son, like the father, rules unopposed.

Noah Berlatsky is the author of Wonder Woman: Bondage and Feminism in the Marston/Peter Comics (Rutgers University Press).

For my money, Levin’s best works were This Perfect Day and The Boys from Brazil. He’s such a bleak writer!

It might be worth pointing out that the author’s own sequel, Son of Rosemary, is completely insane. Rosemary has been in a coma for decades, wakes up in 1999 to see her demonic child an adult, and spends much of the book calmly pondering whether to have sex with him. Then you have a truly outrageous twist ending, that makes nonsense out of everything in the first novel.

Ah, yes, @3 – Son of Rosemary was pretty nonsensical!

A friend and I rented this movie (I would have been in high school or college – it’s been a long time) as we generally enjoyed horror movies, and while I definitely remember some of that psychological horror of having no agency or support (and the marital rape) I never articulated it in such terms and this definitely tracks. I although I do want to add that I don’t find considering abortion a non-starter, or even Rosemary’s instinct to care for her child, to be some automatic patriarchy thing. In a way the desire/willingness to protect the vulnerable even over and above yourself is what helps make civilization possible. Which of course nobody in Rosemary’s life is willing to do on her account, including her own husband – if I recall, wasn’t there an implication that he agreed with the whole thing in the first place in exchange for his career taking off? (Related: I wonder if anybody has ever tried to subvert this kind of story with the idea that maybe Satan’s chosen one doesn’t really want to be Satan’s chosen one if somebody would just give him a chance. Good Omens maybe? It at least plays with this trope).